Macroeconomic instability: cyclicality, unemployment, inflation. Macroeconomic instability. Unemployment and inflation Unemployment: essence, types, consequences

Introduction 4

1. Economic cycles 6

2. Unemployment 9

3. Inflation 16

Conclusion 27

References 31

INTRODUCTION

“The ideas of economists... are much more important than is commonly thought.

In reality, they are the only ones who rule the world."

John Maynard Keynes

Every science has its own object of knowledge. This fully applies to economic science. A characteristic feature of the latter is that it is one of the most ancient sciences. The origins of economic science go back centuries, to the place where the cradle of world civilization was born - to the countries of the Ancient East of the 5th-3rd centuries. BC. Later, economic thought was developed in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Aristotle introduced the term “economy” (from the gr. Oikonomia - household management), from which the later word “economics” came. In the early Middle Ages, Christianity declared simple work to be a holy work, and the most important principle began to be established: he who does not work, does not eat.

As a science, economics arose in the 16th-17th centuries. Her first theoretical direction was mercantilism, who saw the substance of the wealth of society and the individual in money, and reduced money to gold. In the 17th century a new name for economic science appeared - political Economy, (interaction between economics and politics), which lasted for more than three centuries. A new direction was given to this science physiocrats(A. Turgot, F. Quesnay, etc.), who argued that the source of wealth is not exchange, but agricultural labor. The founder of classical political economy was the Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723-1790), who published his famous book “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations” in 1776. At the heart of his concept is the idea of \u200b\u200b“unequal equality”, which attached decisive importance to the division of labor and, as a result, laid the foundations of the labor theory of value and the market economy as a whole ( macroeconomics). A. Smith's teaching was further developed in the works of the German philosopher and economist Karl Marx (1818-1883), who created the theory of scientific socialism in his multi-volume work "Capital".

Modern economic science today has received a more common name - economic theory, and in Anglo-American literature - " economics". The term "economics", which was first introduced by the English economist Alfred Marshall (1842-1924) in his book "Principles of Economics", is understood as the analytical science of using the limited resources of a family, enterprise and society as a whole for the production of various goods, their distribution and exchange between members of society for the purpose of consumption, i.e. in order to satisfy human needs. It is A. Marshall who is considered the “founder” of microanalysis, microeconomics– a direction of economic science that studies and analyzes the activities of individual economic entities and the system of decisions they make.

The Great Depression of 1929-1933 returned the world community to consider the functioning of the national economy as a whole, from the perspective of macroeconomics. A new understanding of the possibilities of a market economy is emerging, it has become clear: it is necessary to introduce a corrective, controlling function of the state, government, and the concept of “economic policy” is emerging. Economic policy is “...a set of measures aimed at streamlining the course of economic processes, influencing them or directly predetermining their course” - Hirsch. The fundamental task is to ensure general equilibrium, i.e. economic and social balance.

It should be noted that macroeconomic disequilibrium is a normal, common and even necessary phenomenon, since economic processes always develop with certain fluctuations and are implemented according to indicators: supply and demand, price movements, unemployment, etc. This work will examine the macroeconomic indicators of economic theory, namely economic cycles, unemployment, inflation, their prerequisites, consequences, and relationships.

1. ECONOMIC CYCLES

"Throughout the history of the literature on business cycles, various economists have time and again expressed the view that the origin of cyclical fluctuations remains an insoluble mystery."

Alvin Hansen

The term "business cycle" refers to successive ups and downs in levels of economic activity, as represented by real GDP.

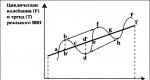

Rice. 1. Trend and cyclical fluctuations of real GDP:

The graph (Fig. 1) shows trend(trend) by connecting the points of real GDP (at the potential level) at the beginning of the study period t 1 and the end of the period tn and a wavy line (F) reflecting fluctuations in the level of GDP caused by the existence of economic cycles. Distance between peak points bf and "bottom" points dh stands for duration cycle. Distance from turning points vertically to the trend line – bb" And dd", measures amplitude cyclical fluctuations.

It is customary to distinguish four phases of the economic cycle: crisis - segment bc; depression - CD; revival - de; climb - ef. You can often come across a simpler classification of cycle phases, which distinguishes downward phases - recession bd and upward – revival df.

It should be noted that a recession does not always entail serious and prolonged unemployment, and the peak of the cycle does not always entail full employment. Despite the phases common to all cycles, individual economic cycles differ significantly from each other in duration and intensity. Therefore, some economists prefer to distinguish three main types of cycles:

· " Short term economic cycles" – regularity 3-4 years. Clearly expressed in cycles of D. Kitchin(1861-1932) and cycles of W. Mitchell (1874-1948);

· " Medium term economic cycles" - regularity, approximately 8-12 years. These cycles are easier than others to observe in a historical context due to their relative regularity and accompanying significant economic shocks, in contrast to short-term cycles. It is generally accepted that the reason for the existence of medium-term cycles is the timing of physical deterioration of fixed assets , but there are other theories, for example, cycles of K. Juglar(1819-1908), in which the reason is interpreted as a set of certain features in the field of banking.

· " Long economic cycles" - regularity 40-50 years. Reasons for cyclicity according to long waves N.D. Kondratieva(1892-1938) – accumulation of capital to replace long-existing means of production. Also, there is no doubt about the direct involvement of developments in the field of scientific and technological progress and, as a consequence, a radical restructuring of production to a qualitatively different level.

Although initial causal factors such as technological innovation, political events, and money accumulation have been used to explain the cyclical development of the economy, it is generally believed that the direct determinant of national output and employment is the volume of total expenditure.

In a primarily market-oriented economy, businesses produce goods and services only if they can be sold profitably; if overall costs are low, many businesses do not benefit from producing goods and services in large quantities. Hence the low level of production, employment and income. A higher level of total spending means that increased production generates profits, so production, employment and income will also increase. When the economy reaches full employment, real output becomes constant, and additional spending simply raises the price level.

All sectors of the economy are affected differently and to varying degrees by the business cycle. The cycle has a stronger impact on output and employment in industries that produce capital goods and durable goods than in industries that produce nondurable goods. When the economy begins to struggle, manufacturers often stop purchasing modern equipment and building new factories. In such a situation, there is simply no point in increasing inventories of investment goods. When the family budget has to be cut, the first thing that goes down is the cost of purchasing durable goods, such as household appliances and cars. People don't buy new models. The situation is different with food products and clothing, that is, non-durable consumer goods. The family must eat and these purchases will decrease and their quality will deteriorate, but not to the same extent as durable goods.

Most industries producing capital goods and durable goods are highly concentrated, with a relatively small number of large firms dominating the market. As a result, such firms have sufficient monopoly power to counteract price declines over a certain period by limiting output due to falling demand. Therefore, the reduction in demand mainly affects production and employment. We see the opposite picture in industries producing non-durable goods (“soft goods”). These industries are mostly quite competitive and characterized by low concentration. They cannot counteract rising prices, and the fall in demand is reflected more in prices than in production levels.

2. UNEMPLOYMENT

"Unemployment as such, whether provided or flooded with private or public subsidies, humiliates a person and makes him unhappy."

Ivan Ilyin

A socio-economic phenomenon in which those who want to work cannot find work at the normal wage rate, i.e. part of the working population is not employed in the process of producing goods.

Concept " full employment" is difficult to define. At first glance, it can be interpreted in the sense that the entire self-employed population, that is, 100% of the labor force, has a job. But this is not so. A certain level of unemployment is considered normal, or justified.

Unemployment rate– the percentage of unemployed people in the labor force, which does not include students, pensioners, prisoners, as well as boys and girls under 16 years of age.

Overall unemployment rate– the percentage of unemployed people to the total labor force, including persons engaged in active military service.

There are several types of unemployment:

· Frictional unemployment

If a person is given the freedom to choose the type of activity and place of work, at any given moment some workers find themselves in a position “between jobs”. Some voluntarily change jobs. Others are looking for new jobs because they were laid off. Still others temporarily lose seasonal jobs (for example, in the construction industry due to bad weather or in the automobile industry due to model changes). And there is a category of workers, especially young people, who are looking for work for the first time. When all these people find a job or return to their old one after being temporarily laid off, other "seekers" of work and temporarily laid off workers replace them in the "general pool of unemployed." Therefore, although specific people left without work for one reason or another replace each other from month to month, this type of unemployment remains.

Economists use the term frictional unemployment for workers who are looking for work or expecting work in the near future. The definition of “frictional” accurately reflects the essence of the phenomenon: the labor market functions clumsily, creakingly, without bringing the number of workers and jobs into line.

Frictional unemployment is considered inevitable and to some extent desirable. Why desirable? Because many workers who voluntarily find themselves “between jobs” move from low-paying, low-productivity jobs to higher-paying, more productive jobs. This means higher incomes for workers and a more rational distribution of labor resources, and therefore a larger real volume of national product.

· Structural unemployment.

Frictional unemployment quietly moves into the second category, which is called structural unemployment. Economists use the term "structural" to mean "composite." Over time, important changes occur in the structure of consumer demand and in technology, which, in turn, change the structure of overall labor demand. Due to such changes, the demand for some types of professions decreases or ceases altogether. Demand for other professions, including new ones that previously did not exist, is increasing. Unemployment arises because the labor force is slow to respond and its structure does not fully correspond to the new job structure. The result is that some workers do not have marketable skills and their skills and experience have become obsolete and redundant due to changes in technology and consumer demand. In addition, the geographic distribution of jobs is constantly changing. This is evidenced by the migration in industry from the "snow belt" to the "sun belt" over the past decades.

Examples: 1. Many years ago, highly skilled glassblowers were left out of work due to the invention of machines used to make bottles. 2. More recently, in the southern states, unskilled and insufficiently educated blacks were forced out of agriculture as a result of its mechanization. Many were left without work due to insufficient qualifications. 3. An American shoemaker, left unemployed due to competition from imported products, cannot become, for example, a computer programmer without undergoing serious retraining, and perhaps without changing his place of residence.

The difference between frictional and structural unemployment is very vague. The significant difference is that the “frictional” unemployed have skills that they can sell, while the “structural” unemployed cannot immediately get a job without retraining, additional training, or even a change of place of residence; Frictional unemployment is more short-term in nature, while structural unemployment is more long-term and therefore considered more severe.

· Cyclical unemployment

By cyclical unemployment we mean unemployment caused by a recession, that is, that phase of the economic cycle that is characterized by insufficient general, or aggregate, spending. When aggregate demand for goods and services decreases, employment falls and unemployment rises. For this reason, cyclical unemployment is sometimes called demand-side unemployment. For example, in the USA, during the recession of 1982. the unemployment rate rose to 9.7%. At the height of the Great Depression of 1933. cyclical unemployment reached approximately 25%. Bankruptcies of enterprises in various fields of economic activity are becoming widespread, and during this period many millions of people, completely unexpectedly and suddenly, become unemployed. The problem is aggravated by the fact that in conditions of cyclical unemployment, people are not helped either by reorientation or training for some new qualification. Changing your place of residence does not always help, because a crisis can cover the entire national economy and even reach the global level.

Cyclical unemployment is also dangerous because, in addition to social disasters, it also brings obvious losses in real GDP. The famous American economist Arthur Okun (1928-1979) drew attention to this. He formulated a law according to which a country loses 2 to 3% of actual GDP relative to potential GDP when the actual unemployment rate increases by 1% above its natural rate. In economic literature this law is known as Okun's law :

(Y – Y*) /Y* = - l (U – U n) ,

Where Y- actual GDP, Y*- potential GDP, U - actual unemployment rate, U n - natural unemployment rate, l (in absolute terms) is the empirical coefficient of sensitivity of GDP to changes in cyclical unemployment (Oken's coefficient).

Suppose the natural rate of unemployment is 5% and its actual rate is 8%. Let's say the Okun coefficient is -2.5. Then the gap between actual GDP and potential GDP will be (8% -5%) x -2.5 = -7.5%: the country “lost” 7.5% of potential GDP.

Now let's look at the concept " full employment"population and let's start with what we call" employment level", namely, the percentage of employed persons to the adult population not on social security, in shelters, nursing homes, etc.

Full employment does not mean absolutely no unemployment. Economists consider frictional and structural unemployment to be completely inevitable: therefore, the unemployment rate at full employment is equal to the sum of the frictional and structural unemployment rates. In other words, the full employment unemployment rate occurs when cyclical unemployment is zero. The full employment unemployment rate is also called natural rate of unemployment. The real volume of national product, which is associated with the natural rate of unemployment, is called the productive potential of the economy. This is the real volume of output that the economy is able to produce with “full use” of labor resources.

The full, or natural, rate of unemployment occurs when labor markets are balanced, that is, when the number of job seekers equals the number of available jobs. The natural rate of unemployment is to some extent a positive phenomenon. After all, the “frictional” unemployed need time to find appropriate vacancies. “Structural” unemployed people also need time to gain qualifications or move to another location when necessary to get a job. If the number of job seekers exceeds the available vacancies, then labor markets are not balanced; At the same time, there is a deficit in aggregate demand and cyclical unemployment. On the other hand, with excess aggregate demand, there is a “shortage” of labor, that is, the number of available jobs exceeds the number of workers looking for work. In such a situation, the actual unemployment rate is below the natural rate. The unusually “tense” situation in labor markets is also associated with inflation.

The concept of “natural rate of unemployment” requires clarification in two aspects.

First, this term does not mean that the economy always operates at the natural rate of unemployment and thereby realizes its productive potential. Unemployment rates often exceed the natural rate. On the other hand, in rare cases, an economy may experience a level of unemployment that is below the natural rate. For example, during the Second World War, when the natural rate was on the order of 3-4%, the demands of war production led to an almost unlimited demand for labor. Overtime and part-time work have become commonplace. Moreover, the government did not allow workers in “essential” industries to quit, artificially reducing frictional unemployment. The actual unemployment rate for the entire period from 1943 to 1945 was less than 2%, and in 1944 it fell to 1.2%. The economy was exceeding its production capacity but was putting significant inflationary pressure on output.

Secondly, the natural rate of unemployment in itself is not necessarily constant; it is subject to revision due to institutional changes (changes in the laws and customs of society). For example, in the 1960s, many believed that this inevitable minimum of frictional and structural unemployment was 4% of the labor force. In other words, it was recognized that full employment had been achieved when 96% of the labor force was employed. And currently, economists believe that the natural rate of unemployment is approximately 5-6%.

Why is the natural rate of unemployment higher today than in the 60s? First, the demographic composition of the workforce has changed. In particular, women and young workers, who have traditionally had a high proportion of unemployed, have become a relatively more important component of the labor force. Secondly, institutional changes have occurred. For example, the unemployment compensation program was expanded both in the number of workers it covered and in the amount of benefits. This is important because unemployment compensation, by weakening its impact on the economy, allows the unemployed to more easily look for work and thereby increases frictional unemployment and the overall unemployment rate.

The debate over the definition of the full employment unemployment rate is exacerbated by the fact that in practice it is difficult to determine the actual unemployment rate. The entire population is divided into three large groups. The first includes persons under 16 years of age, as well as persons in specialized institutions - i.e. persons who are not considered potential components of the labor force. The second group consists of adults who potentially have the opportunity to work, but for some reason are not working and are not looking for work. The third group is the labor force, this group includes people who can and want to work. The labor force is considered to consist of those who are employed and those who are unemployed but actively seeking work.

The unemployment rate is the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed.

The Labor Ministry's statistical office is trying to determine the number of people working and unemployed by conducting monthly sample surveys of about 60,000 families nationwide.

An accurate estimate of the unemployment rate is complicated by the following factors:

1. Part-time employment. In official statistics, all part-time workers are included in the category of full-time workers. By counting them as fully employed, official statistics underestimate the unemployment rate.

2. Workers who have lost hope of getting a job. By not including workers who have lost hope of getting a job in the category of unemployed, official statistics underestimate the unemployment rate.

3. Fake information. The unemployment rate can be inflated when some unemployed people claim that they are looking for work when this is not true, and the shadow economy also contributes to inflating the official unemployment rate.

Conclusion : Although the unemployment rate is one of the most important indicators of a country's economic health, it cannot be considered an infallible barometer of the health of our economy.

There is a huge difference in unemployment and inflation rates in different countries. Unemployment rates differ because countries have different natural unemployment rates and are often in different phases of the business cycle. Over the past several years, inflation and unemployment rates in the United States have been low compared to a number of other industrialized countries.

Average unemployment and inflation rates for nine countries over a five-year period:

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

3. INFLATION

"It was during inflation. I received 200 billion marks a month.

Money was given out twice a day and then there was a break for half an hour - so that they had time to go shopping and buy at least something before the new dollar exchange rate was announced, after which the money depreciated by half."

Erich M. Remarque "Three Comrades"

Inflation is a continuous increase in average price level for all goods and services. Measuring the price level is important for two reasons. First, it is important for us to know how the price level has changed over a certain period of time. Second, since GNP represents the market value, or otherwise the monetary value, of all final goods and services produced during the year, monetary measures are used as the most common indicators in reducing the disparate components of total output to a single basis.

The price level is expressed as an index. Price index is a measure of the relationship between the total price of a certain set of goods and services called " market or consumer basket"(The Law "On the Consumer Basket for the Russian Federation as a Whole" was adopted by the State Duma on October 27, 1999, approved by the Federation Council on November 11, 1999, entered into force on November 23, 1999, valid until December 31, 2000), for this time period and the total price of an identical or similar group of goods and services in the base period. The specified benchmark, or initial level, is called the “base year.” If we represent this in the form of a formula, we get:

The best known among these indices is consumer price index (CPI), calculated for a group of goods and services included in the consumer basket of the average urban resident . In the United States, the consumer price index is calculated based on the prices of 265 goods and services in 85 cities across the country. In general terms, the consumer price index can be represented as the ratio of the base year consumer basket, valued at current prices, to the base year consumer basket, valued at base year prices.

If we conditionally designate the three blocks included in the consumer basket as: “Food” – food; “Non-food products” – clothing; “Services” - housing, then the calculation of the consumer price index will look like it is presented in the table.

| Quantity (1982) |

Production volume 1982 in 1982 prices |

Production volume 1982 in 1992 prices |

|||

CPI = 4100/1950 * 100% = 210.3%

The Consumer Price Index is the most widely used price index. It plays a vital role in the economy, since it is the basis for the recalculation of wages, government payments and many other payments, and therefore, the economy needs a unified method for calculating it, which at the same time would objectively reflect changes in the price level.

For example, let's look at the method for calculating PPI, which is correct from a mathematical point of view and is recommended for calculating PPI, but gives a slightly different result than in the previous case. The starting formula is as follows:

CPI = (food price 1992 / food price 1982) * 100 * food share +

+ (price of clothes 1992 / price of clothes 1982) * 100 * share of clothes +

+ (housing price 1992 / housing price 1982) * 100 * housing share.

By determining the share of each group in the consumer basket and substituting prices, we get:

CPI = 5/2 * 100 * 0.47 + 10/5 * 100 * 0.35 + 20/10 * 100 * 0.18 = 117.5 + 70 + 36 = 223.5

Statistical accuracy requires a single base when calculating indices, and in this regard, the consumer price index is based on a single base - the base year's production volume in the first case, or the single shares of individual goods in the consumer basket in the second case. In this regard, the consumer price index does not reflect how changes in price affect changes in the share of consumption of a particular product. In addition, the price index is not able to estimate what share in the price increase is occupied by qualitative improvements in the product. For example, a car made in 1950 and a car made in 1992 have significantly different quality characteristics. The CPI differs from the GNP deflator in that the GNP deflator estimates the value of current output at current prices. In addition, the GNP deflator is associated with goods and services that form GNP, and the CPI is associated only with those goods and services that are included in the consumer basket.

The price index is one of the main parameters when measuring inflation. For example, in 1987 The consumer price index was 113.6, and in 1988. – 118.3. The inflation rate for 1988 is calculated as follows:

The so-called "magnitude rule of 70" allows you to quickly calculate the approximate number of years required for the price level to double. You just need to divide the number 70 by the annual inflation rate:

Economists distinguish two types of inflation.

· Demand inflation. Traditionally, changes in the price level are explained by excess aggregate demand. An economy may try to spend more than it can produce; it may tend to some point outside its production possibilities curve. The manufacturing sector is unable to respond to this excess demand by increasing real output because all available resources have already been fully used. Therefore, this excess demand leads to inflated prices for a constant, real volume of production and causes demand inflation. The essence of demand inflation is sometimes explained in one phrase: “Too much money chasing too few goods.”

· Inflation caused by rising production costs or a decrease in aggregate supply . Inflation can also result from changes in costs and supply in the market. There have been several periods in recent years when the price level has risen, despite the fact that aggregate demand was not excessive. There were periods when both output and employment (evidence of insufficient aggregate demand) decreased while the general price level increased.

The theory of cost-push inflation explains price increases by factors that increase unit costs. Unit costs are the average costs for a given volume of production. Such costs can be obtained by dividing the total cost of resources by the amount of output produced, that is:

Increasing unit costs in the economy reduces profits and the amount of output that firms are willing to offer at the existing price level. As a result, the supply of goods and services throughout the economy decreases. This decrease in supply, in turn, increases the price level. Therefore, according to this scheme, costs, and not demand, inflate prices, as happens with demand inflation.

The two most important sources of cost-push inflation are increases in nominal wages and in the prices of raw materials and energy.

Wage inflation is a type of cost-push inflation. Under certain circumstances, trade unions can become a source of inflation. This is because they exercise some degree of control over nominal wages through collective bargaining agreements. Let's assume that the big unions demand and get big wage increases. Moreover, let's assume that with this increase they will set a new standard for the wages of workers who are not union members. If a national wage increase is not counterbalanced by some countervailing factor, such as an increase in output per hour, then unit costs will increase. Manufacturers will respond by reducing the production of goods and services released onto the market. Assuming constant demand, this decrease in supply will lead to an increase in the price level.

Supply-side inflation is the other main type of cost-driven inflation. It is a consequence of an increase in production costs, and therefore prices, which is associated with a sudden, unforeseen increase in the cost of raw materials or energy costs. A convincing example is the significant increase in prices for imported oil in 1973–1974. and in 1979 – 1980. As energy prices increased during this time, the production and transportation costs of all output in the economy also increased. This led to rapid growth in cost-driven inflation.

In the real world, the situation is much more complex than the proposed simple division of inflation into two types - demand-driven inflation and cost-driven inflation. In practice it is difficult to distinguish between the two types. For example, suppose military spending increases sharply and therefore incentives to increase demand in goods and resource markets increase, some firms find that their costs for wages, materials, and fuel increase. In their own interests, they are forced to raise prices because production costs have increased. Although there is clearly demand-pull inflation in this case, for many businesses it looks like cost-push inflation. It is difficult to determine the type of inflation without knowing the primary source, that is, the real reason for rising prices and wages.

Most economists believe that cost-push inflation and demand-pull inflation differ in another important respect. Demand-pull inflation continues as long as there is excessive total spending. On the other hand, inflation caused by rising costs automatically limits itself, that is, it either gradually disappears or heals itself. This is because as supply decreases, real national output and employment are reduced, limiting further increases in costs. In other words, cost-driven inflation generates a recession, and the recession, in turn, restrains additional increases in costs.

It is also necessary to note the negative consequences associated with a long-term increase in the average price level. One of the main negative phenomena is the effect of redistribution of income and wealth. This process is possible, first of all, in conditions where income is not indexed, and loans are provided without taking into account the expected level of inflation. Another serious consequence of inflation is the inability to make absolutely correct decisions when developing capital investment projects, which reduces interest in financing them. The damage from inflation is directly related to its size. Moderate inflation does not bring harm; moreover, the reduction in inflation is associated with rising unemployment and a reduction in the real national product. The greatest harm is caused by hyperinflation, the appearance of which is associated with social cataclysms and the rise to power of totalitarian regimes.

The relationship between the price level and the volume of national production can be interpreted in two ways. Typically, real national output and the price level rose or fell simultaneously. However, in the last 20 years or so, there have been several instances where real national output has fallen while prices have continued to rise. Let's forget about this for a moment and assume that at full employment real national output is constant. By holding real national output and income constant, it is easier to isolate the effect of inflation on the distribution of these incomes. If the size of the pie—national income—is constant, how does inflation affect the size of the pieces that go to different segments of the population?

It is extremely important to understand the difference between monetary, or nominal income And real income. Monetary, or nominal, income is the number of units of national currency that a person receives in the form of wages, rent, interest or profit. Real income is determined by the number of goods and services that can be purchased with nominal income. If your nominal income increases at a faster rate than the price level, then your real income will increase and vice versa. The measurement of real income can be roughly expressed by the following formula:

The very fact of inflation - a decrease in the purchasing power of the national currency, that is, a decrease in the number of goods and services that can be purchased per unit - does not necessarily lead to a decrease in personal, real income, or standard of living. Inflation reduces the purchasing power of a currency; however, your real income, or standard of living, will only decline if your nominal income lags behind inflation.

It should be noted that inflation affects redistribution differently depending on whether it is expected or unexpected. In the event of expected inflation, the income recipient can take steps to prevent or reduce the negative effects of inflation that would otherwise affect his real income.

Inflation punishes:

People who receive relatively fixed nominal incomes. Congress introduced indexation of Social Security benefits; Social Security payments take into account the consumer price index to prevent the ravages of inflation.

Some hired workers. Those who work in unprofitable industries and lack the support of strong, militant trade unions.

Owners of savings. As prices rise, the real value, or purchasing power, of your rainy day savings will decrease. Of course, almost all forms of savings earn interest, but nevertheless, the value of savings will fall if the rate of inflation exceeds the interest rate.

Benefits from inflation can go to:

People living on unfixed incomes. The nominal incomes of such families may overtake the price level, or cost of living, causing their real incomes to increase.

Firm managers and other profit recipients. If the prices of finished products rise faster than the prices of inputs, then the firm's cash receipts will grow at a faster rate than its costs. Therefore, some earnings in the form of profits will outpace the rising tide of inflation.

Inflation also redistributes income between debtors and creditors. In particular, unexpected inflation benefits debtors at the expense of creditors.

The distributional consequences of inflation would be less severe and even avoidable if people could 1) anticipate inflation and 2) be able to adjust their nominal incomes to account for impending changes in the price level. For example, persistent inflation that began in the late 1960s led many unions in the 1970s to insist that labor contracts include cost-of-living amendments that automatically adjust workers' earnings for inflation. If you anticipate the onset of inflation, you can also make changes to the distribution of income between creditor and debtor. For this reason, savings and loan institutions introduced variable rate mortgages to protect themselves from the negative effects of inflation. There is a difference between the real interest rate, on the one hand, and the money, or nominal, interest rate, on the other.

Real interest rate is the percentage increase in purchasing power that the lender receives from the borrower.

Nominal interest rate- This is a percentage increase in the amount of money that the lender receives.

So, for example, for a lender to receive a 5% real profit on a loan given an assumed inflation of 6%, he should be assigned a nominal interest rate of 11%. In other words, the nominal interest rate is equal to the sum of the real interest rate and the premium paid to offset the expected rate of inflation.

The impact of inflation on the volume of national product can be considered in three models, in the first of which inflation is accompanied by an increase in the volume of national production, and in the other two – by a decrease.

· Demand inflation concept suggests that if an economy strives for high levels of output and employment, then moderate (or creeping) inflation is necessary. Moderate inflation – This is inflation, in which price increases are no more than 10% annually, and does not cause serious concern to the population and entrepreneurs, since the interest rate on capital markets is quite high, which allows contracts to be concluded in nominal terms.

Rice. 2. Philips curve in the short term:

The inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment was discovered by Alban Phillips, a professor at the London School of Economics. Having examined British statistical data for almost a hundred years (from 1861 to 1957), he came to the conclusion that the rate of growth in prices and wages began to decline if unemployment exceeded the 3% level, and vice versa. In 1958, Phillips published his observations and calculated the inverse relationship between the level of employment and the nominal wage rate. The graphical representation of this dependence is called Phillips curve , which is described as

(w t - w t-1) / w t-1 = - b (N* - Nt) / N*,

Where w - nominal wage rate, b- a parameter reflecting the sensitivity of the level of nominal wages to changes in the unemployment rate, N* - full employment level (corresponding to the natural rate of unemployment).

Phillips' calculations were supported by the theoretical developments of the American economist R. Lipsey. Later, P. Samuelson and R. Solow replaced the growth rate of nominal wages with an inflation rate in the Phillips model p. In this form, the Phillips model, reflecting the relationship between inflation and unemployment, is shown in Fig. 2.

The Phillips curve shows the inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment in the short term: if at the inflation rate p 1 unemployment is at the level U1, then suppressing inflation to p 2 accompanied by rising unemployment U 2.

From the graph (Fig. 2) it is clear that the inflation rate p, plotted on the y-axis, and the unemployment rate U, marked on the x-axis, are inversely related. In the short term, inflationary increases in prices and wages stimulate labor supply and expansion of production.

· Cost-push inflation and unemployment. Let's consider the circumstances under which inflation can cause a reduction in both output and employment. Assume that, from the outset, spending is such that the economy has full employment and a stable price level. If inflation begins, caused by rising costs, then at the existing level of aggregate demand, the real volume of production will decrease. This means that rising costs will cause a sharp increase in prices and, given the total costs, only part of the real product can be purchased on the market. Consequently, real output will decrease and unemployment will increase.

· Galloping inflation limited to 10 to 100% per year. Money depreciates quite quickly, so prices for transactions are denominated in a stable currency, tied to it, or the prices take into account the expected inflation rate at the time of payment.

· Hyperinflation in countries with developed market economies is determined by rates exceeding 100%. For countries with unstable, developing or transition economies, the criterion for the onset of hyperinflation is much higher, for example, in Russia in 1992, inflation rates reached 1353% per year, but were officially recognized as only close to hyperinflation. Proponents of the concept of cost-driven inflation argue that moderate, creeping inflation, which may initially accompany an economic recovery, will then snowball and turn into a more severe one - hyperinflation. It leads to the destruction of the well-being of the nation and is often the basis for changing the regime of power, usually of a totalitarian nature.

To prevent unused savings and current income from becoming worthless, that is, to get ahead of expected price increases, people are forced to “spend money now.” Businesses do the same when purchasing investment goods. Actions dictated by “inflationary psychosis” increase pressure on prices, and inflation begins to “reproach itself.”

Hyperinflation can accelerate economic collapse. Severe inflation contributes to the fact that efforts are directed not to production, but to speculative activity. Prices can be recalculated daily and even several times a day, and a “flight from money” occurs. It is becoming increasingly profitable for households and businesses to stockpile raw materials and finished products in anticipation of future price increases. But the discrepancy between the quantity of raw materials and finished products and the demand for them leads to increased inflationary pressure. Instead of investing capital in investment goods, producers and individuals, to protect themselves from inflation, acquire non-productive material assets - jewelry, gold and other precious metals, real estate, etc.

In an emergency situation, when prices jump sharply and unevenly, normal economic relations are destroyed, the banking system collapses, and not only production is paralyzed, but also the market mechanism itself. Money actually loses value and ceases to fulfill its functions as a measure of value and a medium of exchange. Production and exchange are suspended, and economic, social, and very possibly political chaos may eventually ensue. Hyperinflation precipitates financial collapse, depression, and social and political unrest. Catastrophic hyperinflation is almost always the result of a government's reckless expansion of the money supply.

CONCLUSION

“Like it or not, the fundamental problems of modern politics are indeed purely economic and cannot be understood without knowledge of economic theory. Only a person who understands the basic issues of economic theory is able to develop an independent opinion on the problems under consideration.”

Ludwig von Mises

Looking at models of demand-side inflation and cost-push inflation, we saw that demand-side inflation in the short term can temporarily increase real output by stimulating labor supply. Cost-push inflation, on the contrary, leads to a fall in real production and a decrease in the demand for labor. Thus, there is a close relationship between the level of employment and the rate of inflation. Hyperinflation, which is usually associated with unwise government policies, can undermine the financial system and precipitate collapse.

The state, as a supervisory body, is necessary to carry out stabilization policy - a set of macroeconomic policy measures aimed at stabilizing the economy at the level of full employment, or potential output. There are a lot of recipes for government intervention in the economy in conditions of macroeconomic instability. However, the general principles of influencing the level of business activity boil down to the following provisions: in conditions of recession, the government should pursue a stimulating policy, and in conditions of recovery, a contractionary macroeconomic policy, trying to prevent a strong “overheating” of the economy (inflationary gap). In other words, the government must smooth out the amplitude of fluctuations in actual GDP around the trend line (see Figure 1 again).

One can compare stabilization policy to shooting at a moving target: the object of government influence (the “target” is the country’s economy) is always in motion. And there is a great danger of missing and not making an accurate shot. And if so, then all stabilization policy measures will turn out to be useless or even harmful. Discussions on this matter have been ongoing by economists up to the present day.

A rein has been put on the “wild” economic cycle that shook the foundations of capitalism in the 19th and early 20th centuries, as Samuelson aptly put it. And therefore, to summarize, we can say that, despite all the difficulties of stabilization policy, it is implemented in all countries of the market economy, while naturally having its own differences associated with what is commonly called the “national model of the economy.” American capitalism differs from Japanese capitalism, and Japanese capitalism differs from the transition economy of Russia. Therefore, there cannot be absolutely universal recipes for stabilization policy. However, knowledge of the basic patterns of cyclical development of the economy is an absolutely necessary prerequisite for effective macroeconomic policy of the government in any country.

In conclusion, I cannot resist citing the main socio-economic indicators of Russia for September 1999 in comparison with previous periods:

Main socio-economic indicators of Russia.

| September

|

January-September 1999 |

For information |

|||||||||||||||

| September |

August

|

September 1998 VC |

January - September 1998 in% compared to January-September 1997 |

||||||||||||||

| September |

August |

||||||||||||||||

| Gross domestic product, billion rubles 1) |

|||||||||||||||||

| Output of products and services from basic industries 2) |

|||||||||||||||||

| Volume of industrial production, billion rubles |

|||||||||||||||||

| Investments in fixed assets |

|||||||||||||||||

| Agricultural products, billion rubles |

|||||||||||||||||

| Commercial cargo turnover of transport enterprises, billion tkm |

|||||||||||||||||

| including railway |

|||||||||||||||||

| Volume of communication services, billion rubles. |

|||||||||||||||||

| Retail trade turnover, billion rubles |

|||||||||||||||||

| Volume of paid services to the population, billion rubles |

|||||||||||||||||

| Foreign trade turnover 3), billion US dollars |

|||||||||||||||||

| including: |

|||||||||||||||||

| export of goods |

|||||||||||||||||

| import of goods |

|||||||||||||||||

| Real disposable cash income |

|||||||||||||||||

| Accrued average salary per employee: |

|||||||||||||||||

| nominal, rubles |

|||||||||||||||||

| real |

|||||||||||||||||

| Total number of unemployed, million people |

|||||||||||||||||

| Number of officially registered unemployed, million people |

|||||||||||||||||

| Consumer price index |

|||||||||||||||||

| Producer Price Index |

|||||||||||||||||

| 1) Assessment for the first half of 1999; dynamics for the first half of the year compared to the corresponding period of the previous year. 2) The index of output of products and services of basic industries (IBO) is calculated on the basis of data on changes in the physical volume of output of industry, agriculture, construction, transport, and retail trade. 3) Data are given for August 1999, relative indicators are given in % for August and January-August at current prices. |

|||||||||||||||||

Changes in the main indicators of production of goods and services

in January-September 1998 and 1999

(in % of the corresponding period of the previous year)

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

· V.M. Sokolinsky. State and economy. M., 1997

· V.M.Sokolinsky, M.N.Isalova. Macroeconomic policy in the transition period. M., 1994

· V.M. Sokolinsky. Psychological foundations of economics. M., 1999

· K. McConnell, S. Brew. Economics, principles, problems and politics. M., 1995

· Course of economic theory. Textbook (edited by M.N. Chepurin and E.A. Kiseleva). Kirov, 1999

· P. Samuelson. Economy. M., 1994

· S. Fischer, R. Dornbusch, R. Schmalenzi. Economy. M., 1993

· Textbook on the fundamentals of economic theory (edited by V.D. Kamaev). M., 1994

· Economy. Textbook (edited by A.S. Bulatov). M., 1997

· Economic theory (political economy). Tutorial. M., 1997 (Financial Academy under the Government of the Russian Federation).

Sincerely, A.A. Grigorov

MACROECONOMIC INSTABILITY

AND INFLATION

1. Introduction

In an ideal economy, real Gross National Product would grow at a fast, sustainable rate. In addition, the price level, as measured by the consumer price index, would remain unchanged or rise very slowly. As a result, unemployment and inflation would be negligible. But experience clearly shows that full employment and stable price levels are not achieved automatically. The purpose of this work is to study the sustainable level of prices and inflation in conditions of macroeconomic instability.

2. Inflation, its definition and measurement.

What is “inflation”? Inflation is an increase in the general price level. This, of course, does not mean that all prices necessarily increase. Even during periods of fairly rapid inflation, some prices may remain relatively stable while others fall. For example, although in 1970-1980. In the West there was a fairly high rate of inflation, prices for goods such as VCRs, digital watches and personal computers were actually reduced. Indeed, one of the main sore spots of inflation is that prices tend to rise very unevenly. Some jump, others rise at a more moderate pace, and others do not rise at all.

Inflation is measured using a price index. The price index determines their general level in relation to the base period.

For example, in the consumer goods price index 1982-1984. are used as a base period for which the price level is set to 100. In 1988, the price index was approximately equal to 118. This means that in 1988 prices were 18% higher than in 1982-1984, or, more simply In other words, a given set of goods that cost $100 in 1982 cost $118 in 1998.

The inflation rate for a given year can be calculated by subtracting last year's price index (1987) from this year's index (1988), dividing the difference by last year's index, and then multiplying by 100. For example, in 1987, the consumer goods price index was equal to 113.6, and in 1998 -188.3. Therefore, the inflation rate for 1988 is calculated as follows:

inflation rate = ------------------ x 100 = 4.1%

The so-called “rule of magnitude 70” gives us another way to quantify inflation. More precisely, it allows you to quickly calculate the number of years required for the price level to double. You just need to divide the number 70 by the annual inflation rate.

For example, at an annual inflation rate of 3%, the price level will double in approximately 23 (70 / 3) years. At 8% inflation, the price level will double in approximately nine (70 / 8) years. It should be noted that the “rule of 70” is usually used when, for example, you need to determine how long it will take for real GNP or your personal savings to double

3. Causes of inflation. Factors in the development of inflation and commodity shortages. Inflation based on demand growth. Inflation based on the growth of monetary production costs.

Economists distinguish between two types of inflation.

1. Demand inflation. Traditionally, changes in the price level are explained by excess aggregate demand. An economy may try to spend more than it can produce; it may tend to some point outside its production possibilities curve. The manufacturing sector is unable to respond to this excess demand by increasing real output because all available resources have already been fully used. Therefore, this excess demand leads to inflated prices for a constant real volume of production and causes demand inflation. The essence of demand inflation is sometimes explained in one phrase: “Too much money to hunt for too little goods.”

The rise in demand inflation can be divided into three stages,

On first stage total expenditure, that is, the sum of consumption, investment, government expenditure and net exports, is so low that the volume of national product falls far short of its maximum level at full employment. In other words, there is a significant lag in the real volume of GNP. Unemployment is high and much of enterprise production capacity is idle. Now suppose that aggregate demand increases. Then output will increase, the unemployment rate will decrease, and the price level will increase little or not change at all. This is explained by the fact that there is a huge amount of idle labor and material resources that can be put into action if existing prices on them. An unemployed person does not ask for an increase in wages when he takes up a job. As a result, production volume increases significantly, but prices do not increase.

As demand continues to rise, the economy enters second phase, moving towards full employment and fuller use of available resources. It should be noted that the price level may begin to rise before full employment is achieved. Why? Because as production expands, stocks of idle resources do not disappear simultaneously in all sectors of the economy and in all industries. Some industries are starting to experience bottlenecks even though most industries have excess capacity. Some industries use up their production capacity earlier than others and cannot respond to further increases in demand for their goods by increasing supply. Therefore, their prices are rising. As demand in the labor market increases, some categories of part-time workers begin to be fully utilized and their wages increase in monetary terms. As a result, production costs increase and firms are forced to raise prices. Tightening labor markets increases unions' collective bargaining power and helps them achieve significant wage increases. Firms are willing to give in to union demands for higher wages because they don't want strikes, especially as the economy heads toward greater and greater prosperity. Additionally, as overall costs increase, higher costs can easily be passed on to the consumer by raising prices. Finally, when full employment is reached, firms are forced to hire less skilled (less productive) workers, causing costs and prices to rise. Inflation that occurs in the second stage is sometimes called “premature” because it begins before the country reaches full employment.

When total expenses reach third stage, full employment applies to all sectors of the economy. All industries can no longer respond to increased demand by increasing output. The real volume of the national product has reached its maximum, and a further increase in demand leads to inflation. Aggregate demand that exceeds society's production capabilities causes an increase in the price level.

If we relate these three stages of demand inflation to nominal and real GNP, we can draw the following conclusions:

At a constant price level (first stage), nominal and real GNP increase to the same extent,

With premature inflation (second stage), nominal GNP must be “deflated” to determine changes in output in physical terms.

With “pure inflation” (the third stage), nominal GNP will increase, sometimes at a rapid pace, while real GNP will remain unchanged.

2. Inflation caused by rising production costs or a decrease in aggregate supply.

Inflation can also arise as a result of changes and supply in the market. There have been several periods in recent years when the price level has increased, despite the fact that aggregate demand was not excessive. We have had periods when both the volume of production and the price level decreased while the general price level increased.

Inflation theory, due to rising costs, explains the rise in prices by such factors that lead to an increase costs per unit of production. Unit costs are the average costs for a given volume of production. Such costs can be obtained by dividing the total resource costs by the quantity of output produced.

Increasing unit costs in the economy reduces profits and the amount of output that firms are willing to offer at the existing price level. As a result, the supply of goods and services throughout the economy decreases. This decrease in supply, in turn, increases the price level. Therefore, in this scheme, costs, and not demand, inflate prices, as happens with demand inflation.

The two most important sources of cost-push inflation are increases in nominal wages and in the prices of raw materials and energy.

Inflation caused by higher wages.

Wage inflation is a type of cost-push inflation. Under certain circumstances, trade unions can become a source of inflation. This is because they exercise some degree of control over nominal wages through collective bargaining agreements. Let's assume that the big unions demand and get bigger wage increases. Moreover, let's assume that with this increase they will set a new standard for the wages of workers who are not union members. If a national wage increase is not counterbalanced by some countervailing factor, such as an increase in output per hour, then unit costs will increase. Manufacturers will respond by reducing the production of goods and services released onto the market. If demand remains constant, this decrease will lead to an increase in the price level. Because the culprit is excessive wage increases, this type of inflation is called wage inflation, which is a type of cost-push inflation.

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation

Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education

"Novgorod State University named after Yaroslav the Wise"

Institute of economics and management

Department of Economic Theory

Coursework for the module

"Macroeconomics"

Macroeconomic instability: unemployment

Supervisor:

Makarevich A. N.

Sycheva O. V.

INTRODUCTION

2.1 Types and forms of unemployment

2.2 Causes of unemployment

CONCLUSION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INTRODUCTION

Every science has its own object of knowledge. This fully applies to economic science. A characteristic feature of the latter is that it is one of the most ancient sciences. The origins of economic science go back centuries, to the place where the cradle of world civilization was born - to the countries of the Ancient East of the 5th-3rd centuries. BC. Later, economic thought was developed in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Aristotle introduced the term “economy” (from the gr. Oikonomia - household management), from which the later word “economics” came. In the early Middle Ages, Christianity declared simple work to be a holy work, and the most important principle began to be established: he who does not work, does not eat.

As a science, economics arose in the 16th-17th centuries. Its first theoretical direction was mercantilism, which saw the substance of the wealth of society and the individual in money, and reduced money to gold. In the 17th century a new name for economic science appeared - political economy (the interaction of economics and politics), which lasted for more than three centuries. A new direction to this science was given by the physiocrats (A. Turgot, F. Quesnay, etc.), who argued that the source of wealth was not exchange, but agricultural labor. The founder of classical political economy was the Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723-1790), who published his famous book “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations” in 1776. At the heart of his concept is the idea of \u200b\u200b“unequal equality”, which attached decisive importance to the division of labor and, as a result, laid the foundations of the labor theory of value and the market economy as a whole (macroeconomics). A. Smith's teaching was further developed in the works of the German philosopher and economist Karl Marx (1818-1883), who created the theory of scientific socialism in his multi-volume work "Capital".

Modern economic science these days has received a more common name - economic theory, and in Anglo-American literature - "economics". The term "economics", which was first introduced by the English economist Alfred Marshall (1842-1924) in his book "Principles of Economics", is understood as the analytical science of using the limited resources of a family, enterprise and society as a whole for the production of various goods, their distribution and exchange between members of society for consumption purposes, i.e. in order to satisfy human needs. It is A. Marshall who is considered the “founder” of microanalysis, microeconomics - a branch of economic science that studies and analyzes the activities of individual economic entities and the system of decisions they make.

The Great Depression of 1929-1933 returned the world community to consider the functioning of the national economy as a whole, from the perspective of macroeconomics. A new understanding of the possibilities of a market economy is emerging, it has become clear: it is necessary to introduce a corrective, controlling function of the state, government, and the concept of “economic policy” is emerging. Economic policy is “...a set of measures aimed at streamlining the course of economic processes, influencing them or directly predetermining their course” - Hirsch. The fundamental task is to ensure general equilibrium, i.e. economic and social balance.

It should be noted that macroeconomic disequilibrium is a normal, common and even necessary phenomenon, since economic processes always develop with certain fluctuations and are implemented according to indicators: supply and demand, price movements, unemployment, etc. This work will examine the macroeconomic indicators of economic theory, namely economic cycles, unemployment, inflation, their prerequisites, consequences, and relationships.

1. ECONOMIC INSTABILITY: BASIC POINTS

macroeconomic instability unemployment

1.1 Concept and manifestations of macroeconomic instability

One of the most important reflections of macroeconomic instability is unemployment. In a market economy, there is always a certain number of people who are unemployed. However, not every non-working person is considered unemployed. In accordance with the methodology of the International Labor Organization, unemployed persons are recognized as persons 16 years of age and older, who in the period under review: did not have a job (gainful occupation); were actively looking for work; were ready to get to work.

Macroeconomic instability is primarily fluctuations in economic activity (economic cycles), the emergence of unemployment, underutilization of production capacity, inflation, state budget deficit, and foreign trade balance deficit. It is characteristic of a market economy. Macroeconomic instability reduces economic efficiency in many ways.

Unemployment is a social phenomenon that involves the lack of work among people who make up the economically active population.

Costs of unemployment:

Lost output is the deviation of actual GDP from potential as a result of underutilization of the total labor force (the higher the unemployment rate, the greater the gap in GDP);

Reduction in federal budget revenues as a result of decreased tax revenues and decreased revenue from the sale of goods;

Direct losses in personal disposable income and a decrease in the standard of living of persons who become unemployed and members of their families;

Increased costs for society to protect workers from losses caused by unemployment: payment of benefits, implementation of programs to stimulate employment growth, professional retraining and employment of the unemployed, etc.

In a market economy there is a tendency towards economic instability, which is expressed in its cyclical development, unemployment, and inflationary rise in prices. Unemployment means inability to find a job.

There are three main causes of unemployment: loss of job (dismissal); voluntary resignation from work; first appearance on the labor market

Thus, unemployment occurs when part of the active population cannot find work and becomes a reserve army of labor. Unemployment increases during economic crises and subsequent depressions as a result of a sharp reduction in labor demand. Like any socio-economic phenomenon, unemployment has natural and random features, essential and superficial characteristics, positive and negative aspects. Their intensity depends on the scale, level, regional specifics, and form of unemployment. The essence of inflation is that the national currency depreciates in relation to goods, services and foreign currencies that maintain the stability of their purchasing power. Nowadays, technological progress does not stand still. Products and services are being improved all the time. In this regard, their value increases, and as a result, the price increases. This shows that the roots of inflation lie in the sphere of production, primarily of high-tech products, and are determined by their quality.

1.2 Cyclicality of economic development as a manifestation of macroeconomic instability

Any form of movement of matter, including economic, is characterized by instability, which manifests itself in the fact that changes in any system object accumulate gradually and the system perceives them calmly, since the fluctuations generated by these changes do not exceed the power of the stabilizing mechanisms of the system. As soon as the dominance of stabilizing factors is disrupted, the connections that kept the system in a calm state are destroyed, the system becomes indignant, and its fluctuations become noticeable. This state characterizes the system as unstable. The frequency of oscillations that disrupt the stability of the system depends both on the state of the system itself and on the strength of the reasons that caused these oscillations.

The economy, like any other system, develops unevenly and in waves. This form of movement is largely explained by the law of diminishing marginal productivity of all factors (resources) of production. For example, in order for the land to produce better results from each hectare, fundamental changes in the technical (technological) basis are necessary. Only then will it make sense to make new investments. Within the framework of existing technology, increasing the efficiency of investments always has a limit, overcoming which is ensured by scientific and technical progress and higher qualifications of workers. The use of scientific and technological progress innovations requires the accumulation of capital. Their introduction into production causes first a rapid increase in the marginal utility of factors of production, then a slowdown in this growth and, finally, a decrease in it. This is how ups and downs occur in the economy. If changes in the technological basis of infrastructure industries occur over long periods of time (structures, bridges, roads, power lines, etc. have a long service life), then we are talking about long waves. If we are talking about machines, machines, equipment, the life of which is much shorter (up to 10 years), they are updated faster. This causes average cycles. Thus, it becomes obvious that the very technological basis of production contains the foundations for wave-like (cyclical) development. But this does not exhaust the reasons for cyclical fluctuations.

The problem of detecting the periodicity of fluctuations in the economy and the reasons that determine it did not leave any of the leading economists of the 19th and 20th centuries indifferent.

|

Theories of the XIX--XX centuries. |

Causes of cyclical fluctuations |

||

|

Theories of social production |

The impossibility of marketing some goods depends on the insufficient volume of production of goods in other industries; Violation of proportionality in social production. |

D. Ricardo |

|

|

Exchange theories |

Speculative operations in commodity and money markets |

M. Evans, K. Juglyar, M. Wirth |

|

|

Theories of distribution |

Poverty creates insufficient demand and crises. The cause of poverty is limited resources and the ability of people to reproduce excessively quickly |

T. Malthus |

|

|

External (external) theories |

Natural phenomena; Changes in the political and social structure; Discovery of new lands, resources, gold deposits; Changes in population growth rates; Scientific and technical discoveries and innovations; Psychology (pessimistic and optimistic expectations) |

Almost all scientists admit E. Hansen et al., A. Pigou et al. I. Schumpeter J.M. Keynes |

|

|

Interval (internal) theories |

Re-accumulation of fixed capital. Expansion and contraction of bank credit. Disproportions between the movement of savings and investments in the industries of the first division, as well as between the organization of production within a separate enterprise or syndicate and the disorganization of all national production |

F. Hayek, L. Mises, etc. N. Huotri, etc. M.I. Tugan-Baranovsky |

Thus, we have examined in the most general form the existing theories of cyclic oscillations of the 19th - first half of the 20th centuries. Scientific interest in models of cyclic oscillations has been revived since the second half of the 20th century. At the beginning of the 21st century. this interest intensified. A wide variety of factors that force the economic system to fluctuate cyclically are studied: different reactions over time of aggregate demand and aggregate supply to changes in the price level; different propensity to save between entrepreneurs and employees; changes in the value of autonomous demand, etc. These models are the object of study in the Macroeconomics course.

2. UNEMPLOYMENT AS A FORM OF MACROECONOMIC INSTABILITY

2.1 Types and forms of unemployment

"Unemployment as such, whether provided or flooded with private or public subsidies, humiliates a person and makes him unhappy."

Ivan Ilyin

A socio-economic phenomenon in which those who want to work cannot find work at the normal wage rate, i.e. part of the working population is not employed in the process of producing goods.

The entire population of the country is divided into two categories: 1) the economically active population, including employed and unemployed; 2) the inactive population, consisting of children, pensioners, students, as well as people who do not want to work (housewives, tramps, idle people, etc.). The percentage of unemployed people in the entire economically active population is called the unemployment rate. It is defined as follows:

where u is the unemployment rate; U is the number of unemployed; L is the total number of labor force (employed plus unemployed).

According to the form of manifestation, unemployment is divided into open and hidden. Open unemployment occurs when a worker is officially fired with a corresponding loss of his working status. With hidden unemployment, people are not formally fired, but are transferred to part-time work, sent on forced leave, work without pay, etc.

There are three main types of unemployment:

Frictional unemployment

If a person is given the freedom to choose the type of activity and place of work, at any given moment some workers find themselves in a position “between jobs”. Some voluntarily change jobs. Others are looking for new jobs because they were laid off. Still others temporarily lose seasonal jobs (for example, in the construction industry due to bad weather or in the automobile industry due to model changes). And there is a category of workers, especially young people, who are looking for work for the first time. When all these people find a job or return to their old one after being temporarily laid off, other "seekers" of work and temporarily laid off workers replace them in the "general pool of unemployed." Therefore, although specific people left without work for one reason or another replace each other from month to month, this type of unemployment remains.

Economists use the term frictional unemployment to refer to workers who are looking for work or expecting to get a job in the near future. The definition of “frictional” accurately reflects the essence of the phenomenon: the labor market functions clumsily, creakingly, without bringing the number of workers and jobs into line.

Frictional unemployment is considered inevitable and to some extent desirable. Why desirable? Because many workers who voluntarily find themselves “between jobs” move from low-paying, low-productivity jobs to higher-paying, more productive jobs. This means higher incomes for workers and a more rational distribution of labor resources, and therefore a larger real volume of national product

Structural unemployment.

Frictional unemployment quietly moves into the second category, which is called structural unemployment. Economists use the term "structural" to mean "composite." Over time, important changes occur in the structure of consumer demand and in technology, which, in turn, change the structure of overall labor demand. Due to such changes, the demand for some types of professions decreases or ceases altogether. Demand for other professions, including new ones that previously did not exist, is increasing. Unemployment arises because the labor force is slow to respond and its structure does not fully correspond to the new job structure. The result is that some workers do not have marketable skills and their skills and experience have become obsolete and redundant due to changes in technology and consumer demand. In addition, the geographic distribution of jobs is constantly changing. This is evidenced by the migration in industry from the "snow belt" to the "sun belt" over the past decades.

Examples: 1. Many years ago, highly skilled glassblowers were left out of work due to the invention of machines used to make bottles. 2. More recently, in the southern states, unskilled and insufficiently educated blacks were forced out of agriculture as a result of its mechanization. Many were left without work due to insufficient qualifications. 3. An American shoemaker, left unemployed due to competition from imported products, cannot become, for example, a computer programmer without undergoing serious retraining, and perhaps without changing his place of residence.

The difference between frictional and structural unemployment is very vague. The significant difference is that the “frictional” unemployed have skills that they can sell, while the “structural” unemployed cannot immediately get a job without retraining, additional training, or even a change of place of residence; Frictional unemployment is more short-term in nature, while structural unemployment is more long-term and therefore considered more severe.

Cyclical unemployment

By cyclical unemployment we mean unemployment caused by a recession, that is, that phase of the economic cycle that is characterized by insufficient general, or aggregate, spending. When aggregate demand for goods and services decreases, employment falls and unemployment rises. For this reason, cyclical unemployment is sometimes called demand-side unemployment. For example, in the USA, during the recession of 1982. the unemployment rate rose to 9.7%. At the height of the Great Depression of 1933. cyclical unemployment reached approximately 25%. Bankruptcies of enterprises in various fields of economic activity are becoming widespread, and during this period many millions of people, completely unexpectedly and suddenly, become unemployed. The problem is aggravated by the fact that in conditions of cyclical unemployment, people are not helped either by reorientation or training for some new qualification. Changing your place of residence does not always help, because a crisis can cover the entire national economy and even reach the global level.

Cyclical unemployment is also dangerous because, in addition to social disasters, it also brings obvious losses in real GDP. The famous American economist Arthur Okun (1928-1979) drew attention to this. He formulated a law according to which a country loses 2 to 3% of actual GDP relative to potential GDP when the actual unemployment rate increases by 1% above its natural rate. In economic literature, this law is known as Okun's law:

(Y - Y*) /Y* = -(U - Un),

where Y is actual GDP, Y* is potential GDP, U is the actual unemployment rate, Un is the natural unemployment rate, (in absolute terms) is the empirical coefficient of sensitivity of GDP to changes in cyclical unemployment (Ouken's coefficient).

Suppose the natural rate of unemployment is 5% and its actual rate is 8%. Let's say the Okun coefficient is -2.5. Then the gap between actual GDP and potential GDP will be (8% -5%) x -2.5 = -7.5%: the country “lost” 7.5% of potential GDP.