Who are otkhodnik peasants? Peasant otkhodniks - definition, history and interesting facts. See what “Otkhodnichestvo” is in other dictionaries

Speaking about migrations, it is necessary to highlight another phenomenon that contributes to population movements – otkhodnichestvo.

Otkhodnichestvo was the name given to the temporary departure of peasants from their places of permanent residence to work in areas of developed industry and agriculture. The peasants themselves who went to work were called “otkhodniks.”

The main reason for otkhodnichestvo was the lack of land. The plots allocated to peasants after the reform of 1861 often did not allow them to feed their families.

Otkhodnichestvo was primarily carried out by the peasants of Central Russia. In non-chernozem provinces (for example, Tver and Novgorod), latrine trades were the main way of earning money for many families. However, small plots of peasants in Tula, Voronezh and other provinces also contributed to leaving to earn money.

According to statistics of that time, in the 1880s. more than 5 million people were engaged in waste trades annually (for comparison, the population of St. Petersburg according to the 1897 census was 1.2 million people). In different provinces the number of otkhodniks ranged from 10 to 50 percent.

The activities of otkhodniks in the cities were connected with several areas. Firstly, they could be factory workers, who numbered from 10 to 35 percent among otkhodniks from different provinces. Secondly, peasants could engage in various construction jobs (for example, be masons, plasterers, carpenters, etc.). Thirdly, otkhodniks could work as servants in taverns or (mostly women) as servants in houses. Finally, most of the cab drivers in the cities came from other provinces.

However, a significant part of the otkhodniks worked in agriculture, being hired as farm laborers. The main directions of migration for such work: Southern Russia and the Northern Caucasus, New Russia (Tavricheskaya, Kherson and Yekaterinoslav provinces).

Otkhodniks usually had a regional specialization. For example, the tavern business in St. Petersburg was associated mainly with immigrants from the Yaroslavl province, and in construction there were many immigrants from the Nizhny Novgorod province. Local history literature will help you determine what your ancestors might have done.

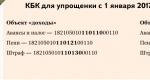

A person could leave his place of residence by receiving a passport. I will tell you about the history of passports in Russia later. Here I note that according to the Charter on Passports of 1895, there were two types of documents for peasants that gave the right to leave: passport books, issued for a period of 5 years to those who had no debts on taxes and fees, and passports, issued for a period of up to one year. years to those who had such arrears and debts.

It is quite difficult to trace migration directions using documents. Thus, in the confessional statements, the absence of men might not be recorded, and the very fact of such a record does not allow us to establish exactly where the person worked.

The most detailed information in this regard is provided by the materials of the 1897 census. It may be indicated that one of the family members is a maid in St. Petersburg or works in a tavern in Moscow.

As for searching through documents for the place where the peasants worked, some searches are also possible here, although their results are very limited. First of all, if the whole family moved, the research can be carried out using parish registers. Searching for places of work usually does not produce results. However, in our practice there was a case when we were able to identify the personal file of a janitor on the railway.

Thus, otkhodnichestvo was widespread in rural areas. Studying archival documents and local history literature will help you determine what your ancestors did.

Since the beginning of the 90s, the phenomenon of otkhodniks—a free labor force moving between big cities and the outback—has been revived in Russia. What does this social phenomenon look like in today's Russia? Is there a threat to the state from the growing number of otkhodniks? Who are these people?

From 50 to 80% of residents of small towns in Russia are forced to go to work in large cities in order to support their families and educate their children. These people most often work unofficially, do not pay taxes, do not use free healthcare, do not count on a pension and actually live “outside the state.” Participants in a project organized by the Khamovniki Foundation for Supporting Social Research spoke about the social and economic roots of this phenomenon at a round table held on October 29.

Otkhodnichestvo as a phenomenon of Russian reality

Sociologists call otkhodnichestvo a special type of labor migration, when one of the family members leaves to work in another city or region. It existed in Russia for several centuries and disappeared only during Soviet times. Waste trades were an important source of income for peasants who left their native villages for a time in order to get hired to work in a mine, a construction site, a factory, barge haulers, etc. At the end of the 19th century. Up to 98% of the working population of the Central Non-Black Earth Region were otkhodniks.

In the late 1990s, when mass closures of enterprises began, residents of villages and small towns again remembered the old crafts of their ancestors, which seemed to be a thing of the past. Over the past decades, there has been a growing number of those who, in an effort to lift their families out of poverty, go to other cities and regions. Such people offer themselves as security guards and builders, lumberjacks or carpenters, sellers, servants, sometimes doctors, educators, teachers and drivers. Today we can say that there is a constantly growing stratum in Russian society; it consists of the most active part of the population - otkhodniks. A special project “Otkhodniks in Small Towns of Russia”, organized and financed by the Khamovniki Foundation for the Support of Social Research and carried out by employees of the Higher School of Economics (NRU-HSE), was dedicated to its study. Research within the project lasted three years. During this time, project participants visited 16 regions, observed, and interviewed otkhodniks themselves, their relatives and neighbors using a special questionnaire. The results of this work are presented in the book “Otkhodniki” by NRU-HSE professor Yuri Plyusnin and young sociologists Natalia Zhidkevich, Yana Zausaeva and Artemy Pozanenko.

According to Yuri Plyusnin, modern otkhodnichestvo is not some new phenomenon, but only a revival of what existed before. Although for most otkhodniks their way of life is forced, among those surveyed there were many who would prefer waste trades, even if they had the opportunity to earn relatively good money at home. “Otkhodniks will always be among us: the state follows the population, the population runs away from the state - this is the centuries-old history of the development of the Russian state,” says Yuri Plyusnin. At the same time, children, as a rule, follow in the footsteps of their parents: children of state employees want to receive money in the public sector, and children of otkhodniks in the future are also ready to engage in waste fishing.

For a not very long ruble

The main reason for going to work is, most often, the desire not just to make ends meet, but to live with dignity - a little better than the neighbors - and most importantly, to educate the children. For many otkhodniks, going on vacation with the whole family is an almost unattainable luxury. Most of them, already tired of constant travel, relax at home, go fishing, and meet with friends.

At the same time, in ruble equivalent, the demands of otkhodniks are quite modest. They are ready to work at their place of residence if their earnings are only 3-5 times higher than the subsistence level, i.e. will be 20-25 thousand rubles - this is only twice as much as public sector workers receive. The official salary of a salesperson in a store in small towns, as a rule, is 5-6 thousand rubles. In production, the salary is slightly higher - 10-15 thousand rubles, but it is also impossible to support a family normally, since prices for manufactured goods and products (with the exception of local gifts of nature) are actually comparable to Moscow.

In reality, otkhodniks earn twice as much as what they are willing to leave home and family for, and 3-4 times more than they could earn at their place of residence. All this allows them to feel wealthier than their neighbors. It is interesting that the expectations of those hired for unskilled work - as security guards - are much higher than, for example, among builders, and their incomes, on the contrary, are lower. As the authors of the book suggest, perhaps the guards watch too much TV, and under its influence they develop inflated needs.

The average asking price is:

At the same time, the otkhodnik has to spend a significant part of the money he earns on food and housing in a foreign land.

"Portrait" of an otkhodnik

Otkhodniks are perhaps the most active part of Russian society. A typical otkhodnik is a well-socialized, highly motivated middle-aged man who is unpretentious in everyday life and resistant to difficult living conditions. He is sociable, mentally developed, drinks little, has a positive outlook on life, and has several children.

Unlike metropolitan residents, otkhodniks see positive things not in the West, not in the experience of other countries, the main value for them is their family, their own home, farm, small estate, which they equip, their work is inseparable from rest, notes the chairman of the expert council Khamovniki Foundation, full professor at the Higher School of Economics Simon Kordonsky.

This generalization is rather arbitrary, since among otkhodniks one can also distinguish different categories: according to their standard of living, qualifications and needs, says Yuri Plyusnin. Low-skilled security guards, for example, are not particularly motivated to work, unlike construction workers or truck drivers. It is the latter who are more altruistic, ready to support relatives, neighbors, acquaintances, and it is this group of people that society can rely on.

Otkhodniks and the state

Otkhodniks find work themselves, usually through friends. In most cases, they have almost no interaction with the state: they work unofficially, do not pay taxes, do not enjoy social benefits and free medical care, and do not count on free education for their children and a pension for themselves. “There is a feeling that even if the state now completely closes education, healthcare, social protection and other socialist institutions, the population in these towns will survive due to otkhodnichestvo and will live peacefully without the state,” notes Simon Kordonsky.

Official statistics practically do not take them into account, and therefore the number of otkhodniks can only be judged approximately. NRU-HSE researchers used several sources for this: official data on employment, approximate estimates of local residents, data from the local press and even information from school class registers, teacher surveys and an amazing document that, it turns out, exists - the school’s social passport. Using all these methods, it turned out that the total number of otkhodniks throughout the country could be 15-20 million families. In most regions, otkhodniks make up more than 50% of the working population, and in some regions - up to 80%. As Deputy Prime Minister Olga Golodets said in April 2013, “out of 86 million citizens of working age, only 48 million work in sectors that are visible to us. We don’t understand where and what the rest are doing.” Thus, according to indirect government estimates, the number of otkhodniks may be about 38 million Russians – i.e. 40% of the country's working population.

“Today this entire huge labor market is in the shadows,” notes Simon Kordsky. “Together with the new business, which through the efforts of our government is again moving into the shadows, a very powerful social group is being formed, active and capable of independent action. Under certain circumstances, it may well manifest itself as a political force.

The state has not yet noticed the otkhodniks and has not affected them, but it is very likely that soon it will come to grips with them, says Evgeniy Gontmakher, deputy director of the Institute of World Economy and International Relations of the Russian Academy of Sciences. “Just a few years ago, even without otkhodniks, there was a lot of money in the budget from oil and gas. If in the coming years there is a decrease in rent flows to the budget, then every otkhodnik will become an object of hunting.

This will be terror against this category, covered with talk of justice. Now all the money from the budget is spent on implementing Putin’s decrees on wages. And sooner or later the roofs in schools and hospitals will leak. Then the otkhodniks will be forced to share by any means, including with the involvement of the security forces. And they can’t run away anywhere with their estates, these are not Old Believers.”

Otkhodniks and the future of Russia

The purpose of the study was only to describe otkhodnichestvo as a phenomenon; giving it any assessment was not the task of scientists - this was done by Evgeniy Gontmakher. In his opinion, otkhodnichestvo is a forced phenomenon that directly contradicts both the needs of the country and a person’s concept of happiness. Contrary to persistently propagated opinions, it is not the settled way of life that is the value. In countries where labor mobility is high, people would like to own a home, live in one place and, if possible, not change jobs. Mobility and labor migration are just a myth. And therefore, the current Russian prime minister’s statement about the benefits of cutting jobs is highly irresponsible.

“Our otkhodnichestvo is a relic. Even in the 17th-18th centuries this was forced. This is the wear and tear of the human capital that still remains in Russia. This is his most barbaric exploitation. Otkhodniks tend to have poor health and potentially live relatively shorter lives than the average citizen. Most otkhodniks would like to live differently.” With all his personal sympathies and respect for these people, Evgeniy Gontmakher assesses the very phenomenon of otkhodnichestvo very negatively - both from a social and economic point of view. “The existence of otkhodnichestvo speaks of the flawed nature of our economic policy. A normal country is a country where there are growth points almost everywhere. The concentration of business activity in Moscow, St. Petersburg and in cities with a population of one million leads to the depopulation of vast territories. If otkhodnichestvo in Russia continues to increase, this will mean its departure from a certain main civilized path of development.”

Meanwhile, these are the trends that are evident today. In particular, with the recently adopted pension reform, the state is actually pushing people out of the state pension system. People will not turn to it and will not even hope for it, because they will understand that they are not able to earn experience or points. We are going back to tsarist times, when the pension system was the privilege of a very small circle of people, the property of the military and a limited circle of skilled workers.

The fact that the current government policy leads not only to the destruction of the economy, but also to the degradation of the population is indirectly evidenced by the materials in the book. The collected interviews talk about the closure of schools and hospitals, the decline in wages due to the influx of cheap labor from Central Asia, and the fact that unskilled work in a foreign land is paid better than skilled work at home. “On the other side of the barricades,” entrepreneurs and local authorities talk about a change in psychology, an unwillingness to work and a lack of qualified personnel. “With equal wages, the work of a turner, milling machine, or welder requires more physical and moral effort than the work of a security guard. Nobody wants to put too much strain on it. Therefore, when jobs are lost there, and skilled jobs appear here, people have no particular desire to return and work here in their working specialties,” notes the head of the Kineshma city administration, A.V., in his interview. Tomilin.

The roads of peasants who temporarily left their native village to earn money on the side crossed Russia in all directions.

They went to close, long and very long distances, from north to south and from west to east. They left to return on time, and brought from foreign places not only money or purchased things, but many impressions, new knowledge and observations, new approaches to life. The village of Suganovo, Kaluga district, is the central part of European Russia, what is called indigenous Rus'. At the end of the 19th century, people left it to earn money in Moscow, Odessa, Nikolaev, Ekaterinoslavl and other cities. Mostly young men, even teenagers, before military service, went on retreat here. It is a rare man in this village who has not gone to work. Sometimes girls also left: as nannies, cooks in the workers' artels of fellow countrymen. But in other places, women's work was generally frowned upon. Here is information from the same time from the Dorogobuzh district of the Smolensk region. Mostly young guys, but also soldiers returning from service, also go to work here. “Almost everyone” engaged in withdrawal on their own accord. This “almost” apparently refers to those cases when the guy was sent to work by his family or by the highway. The deceased certainly sends money to the family. Women, with rare exceptions, never go to work.

And the volosts adjacent to Onega “are distinguished by their skillful and fearless navigators.” If the farm of a peasant family was small and there were more workers in the family than needed, then the “extra” were spent on everyday earnings for a long time, sometimes even three years, leaving the family. But most otkhodniks left their families and households only for that part of the year when there was no field work. In the central region, the most common period of otkhodnichestvo was from the Filippov ritual (November 14/27) to the Annunciation (March 25/April 7). The period was counted according to these milestones, since they were permanent (they did not belong to the movable part of the church calendar). In some seasonal jobs, such as construction, the hiring deadlines could be different. Waste trades were very different - both in types of occupations and in their social essence. A peasant otkhodnik could be a temporary hired worker in a factory or a farm laborer on the farm of a wealthy peasant, or he could also be an independent artisan, contractor, or Gorgov worker. Okhodnichestvo reached a particularly large scale in the Moscow, Vladimir, Tver, Yaroslavl, Kostroma and Kaluga provinces. In them, leaving to earn money outside was already widespread in the last quarter of the 18th century and further increased.

For the entire central region, the main place of attraction for otkhodniks was Moscow. Before the reform, the predominant part of otkhodniks in the central industrial region were landowner peasants. This circumstance deserves special attention when clarifying the possibilities for the interests and real activities of the serf peasant to go beyond the boundaries of his volost. Those who like to speculate about the passivity and attachment to one place of the majority of the population of pre-revolutionary Russia do not seem to notice this phenomenon. The Vladimir province has long been famous for the skills of carpenters and masons, stonemasons and plasterers, roofers and painters. In the 50s of the 19th century, 30 thousand carpenters and 15 thousand masons went to Moscow from this province to work. We went to Belokamennaya in large teams. Usually the head of the artel (contractor) became a peasant “more prosperous and resourceful” than others. He himself selected members of the artel from 165 fellow villagers or residents of nearby villages. Some peasant artel workers took on large contracts in Moscow and assembled artels of several hundred people. Such large artels of builders were divided into parts, under the supervision of foremen, who, in turn, eventually became contractors.

Among the specialties for which the Vladimir peasants on retreat were famous, the peculiar occupation of the ofeni occupied a prominent place. Ofeni are traders of small goods peddling or delivering. They served mainly villages and small towns. They traded mainly in books, icons, paper, popular prints in combination with silk, needles, earrings, rings, etc. Among the Ofeni, their “Ofenian language” had long been in use, in which peddlers of goods spoke among themselves during trade. Otkhodnichestvo for the Ofensky fishery was especially widespread in the Kovrovsky and Vyaznikovsky districts of the Vladimir province. In a description received by the Geographical Society in 1866 from the Vyaznikovsky district, it was reported that many peasants from large families from Uspenye (August 15/28) set off with ophens. They usually “left” for one winter. Others left “even young wives.” By November 21 (December 4), many of them were in a hurry to get to the Vvedenskaya Fair in the Kholui settlement. Vyaznikovsky ofeni went with goods to the “lower” provinces (that is, along the lower Volga), Little Russia (Ukraine) and Siberia. At the end of Lent, many ofeni returned home “with gifts to the family and money as rent.” After Easter, everyone returned from the Ofen fishery and took part in agricultural work. Ofeni-Vyaznikovites were also known outside of Russia. A source from the mid-18th century reported that they had long “traveled with holy icons to distant countries” - to Poland, Greece, “to Slavenia, the Serbs, the Bulgarians” and other places. In the 80s of the 19th century, the people of the Vladimir province bought images in Mstera and Kholuy and sent them in convoys to fairs “from Eastern Siberia to Turkey.”

At the same time, in remote places they accepted orders for the next delivery. The scale of the trade in Vladimir icons in Bulgaria in the last quarter of the 19th century is evidenced by the following curious fact. In the village of Goryachevo (Vladimir province), which specialized in the manufacture of various types of carriages, the Ofeni ordered in the spring of 1881 120 carts of a special design, specially adapted for transporting icons. The carts were intended to transport Palekh, Kholuy and Mstera icons throughout Bulgaria. The Yaroslavl peasants showed great ingenuity in making money in Moscow. They became, in particular, the initiators of setting up vegetable gardens in the wastelands of a big city. The fact is that the Yaroslavl province had rich experience in the development of vegetable gardening. The peasantry of the Rostov district was especially famous in this regard. At the end of the 18th - beginning of the 19th centuries, Rostov peasants already had many vegetable gardens in Moscow and its environs. Only according to annual passports, about 7,000 peasants left the Yaroslavl province in 1853 for gardening. 90 percent of them went to Moscow and St. Petersburg. Ogorodniks (like other otkhodniks) varied greatly in the nature and size of their income. Some Rostov peasants had their own vegetable gardens in Moscow on purchased or leased land. Others were hired as workers by their fellow villagers. Thus, in the 30-50s of the 19th century, in the Sushchevskaya and Basmannaya parts of Moscow, as well as in the Tverskaya-Yamskaya Sloboda, there were extensive vegetable gardens of rich peasants from the village of Porechye, Rostov district.

They made extensive use of hiring their fellow countrymen. Renting out plots to peasant gardeners brought significant income to Moscow land owners. If they were landowners, they sometimes rented out their Moscow land for vegetable gardens to their own serfs. S. M. Golitsyn, for example, rented a large plot of land from his Yaroslavl serf Fyodor Gusev. Often the tenant, in turn, subleased such a plot in small parts to fellow villagers. Yaroslavl peasants in Moscow were engaged in more than just gardening. Frequent among them were also the professions of peddler, shopkeeper, hairdresser, tailor, and especially innkeeper. “The innkeeper is not a Yaroslavl resident - a strange phenomenon, a suspicious creature,” pisa; I. T. Kokorev about Moscow in the forties of the last century. The specialization in waste industries of entire regions or individual villages was noticeably influenced by their geographical location. Thus, in the Ryazan province, in villages close to the Oka, the main latrine industry was barge hauling. Along the Oka and Prona rivers they were also engaged in grain trade. Wealthier peasants participated in the supply of grain to merchants, and poorer peasants, as small trusted merchants (shmyrei), bought small reserves of grain from small landowners and peasants.

Others made money from the carriage industry associated with the grain trade: they delivered grain to the pier. Others worked on the piers, stuffing sculls, loading and unloading ships. In the steppe part of the Ryazan province, the latrine fishery of shertobits successfully developed. Traditions of professional skills have developed here on the basis of local sheep breeding. Sherstobits went to the Don, to the Stavropol region, to Rostov, Novocherkassk and other steppe places. Most of the Sherstobits were in the villages of Durnoy, Semensk, Pronskiye Sloboda, Pecherniki, Troitsky, Fedorovsky and neighboring villages. To beat wool and felt buroks, they went south on carts. Some Sherstobites left their native places for a year, but the majority went to the steppe places only after the grain harvest and until the next spring. In the wooded areas of the same Ryazan region, crafts related to wood prevailed.

However, their specific type depended on the local tradition, which created its own techniques, its own school of skill. Thus, a number of villages in Spassky district specialized in cooperage. The peasants practiced it locally and used their passports to travel to the southern, wine-growing regions of Russia, where their skills were in great demand. The main center of the cooperage industry in Spassky district was the village of Izhevskoye. Izhevsk residents prepared part of the material for making barrels at home. As soon as the river opened up, they loaded large boats with this material in whole batches and sailed to Kazan. In Kazan, the main preparation of cooperage boards took place, after which the Ryazan coopers moved south. In the Yegoryevsky district of the Ryazan province, many villages specialized in the manufacture of wooden reeds, combs and spindles. Reed is an accessory of a weaving machine, a type of comb. Yegoryevites sold berds in rural markets of Ryazan, Vladimir and Moscow provinces. Their main sales were in the southern regions - the Don Army Region and the Caucasus, as well as in the Urals. They were delivered there by buyers from Yegoryevsk peasants, who from generation to generation specialized in this type of trade. In the minds of the residents of the Don and the Caucasus, the occupation of berd-shchik was firmly associated with origins from Yegoryevsk. Bird buyers took goods from their neighbors on credit and sent them on carts to the steppe regions.

About two and a half thousand reeds, spindles and combs were transported on one cart. In places where goods were exported, in villages and other villages, Yegoryevsk peasants had acquaintances and even friends. These relationships were often inherited. Southerners eagerly awaited distant guests at certain times - with their goods, gifts and news stories. Confidence in a friendly welcome, free maintenance from friends, free grazing for tired horses - all this encouraged Yegoryev peasants to maintain this type of otkhodnichestvo. They returned with a significant profit. The lifestyle of peasant otkhodniks in big cities developed its own traditions. This was facilitated by a certain cohesion between them, 167 associated with leaving the same places, and specialization in this type of income on the side. For example, some villages of the Yukhnovsky district of the Smolensk province regularly supplied water carriers to Moscow. In Moscow, Smolensk peasants who came to fish would unite in groups of 10 or even 30 people.

They jointly rented an apartment and a hostess (matka), who prepared food for them and looked after order in the house in the absence of water carriers. Let us note in passing that in the past, the service of large cities by village residents who came there for a while and returned home to their families superficially resembles the same “shuttle” method of work in rural areas that other economists are now thinking about. In part, it is now being implemented not very successfully in temporary “deployments” or collective trips of townspeople to the field. And then he walked in the opposite direction. The majority of the country's population lived in healthy rural conditions. Part of the rural population “shuttle” provided labor for industry (almost all types of industry used the labor of otkhodniks) and, if we use the modern term, the service sector: cab drivers, water carriers, maids, nannies, clerks, innkeepers, shoemakers, tailors, etc. To this should be added , that many of the landowners lived and served in the city temporarily, then returned to their estates.

Contemporaries assessed the significance of otkhodnichestvo in peasant life differently. They often noted the spirit of self-sufficiency and independence among those who worked on the side, especially in big cities, and emphasized the knowledge of otkhodniks in a wide variety of issues. For example, folklorist P. I. Yakushkin, who visited the villages a lot, wrote in the 40s of the 19th century about the Rannenburg district of the Ryazan province: “The people in the district are more educated than in other places, the reason for which is clear - many go to work from here to Moscow, to the Niz (that is, to the districts in the lower reaches of the Volga - M.G.), they are recruiting like crazy.” But many - in articles, private correspondence, responses from the field to the programs of the Geographical Society and the Ethnographic Bureau of Prince Tenishev - expressed concern about the damage to morality that the waste caused. There is no doubt that traveling to new places, working in different conditions and often living in a different environment - all this expanded the peasant’s horizons, enriched him with fresh impressions and diverse knowledge. He got the opportunity to directly see and understand much in the life of cities or rural areas remote and different from his native places. What was known by hearsay became reality. Geographical and social concepts developed, communication took place with a wide range of people who shared their opinions. I. S. Aksakov, driving through the Tambov province in 1844, wrote to his parents: “On the road we came across a coachman who had been to Astrakhan and drove there as a cab. He praised this province very much, calling it popular and cheerful, because there are many tribes there and in the summer men flock from everywhere to fish.

I am amazed how a Russian person bravely goes on a long-distance fishing trip to places that are completely alien, and then returns to his homeland as if nothing had happened.” But the other side of otkhodnichestvo is also quite obvious: families left behind for a long time, the bachelor lifestyle of the deceased, sometimes superficial borrowing of urban culture to the detriment of traditional moral principles instilled by upbringing in the village. I. S. Aksakov, in another letter from the same trip, will write about the Astrakhan otkhodnichestvo from the words of a coachman from a neighboring province: “Whoever goes to Astrakhan once becomes completely different, forgets everything about the house and joins an artel consisting of 50, 100 or more people.

The artel has everything in common; approaching the city, she hangs out her badges, and the merchants rush to open their gates to them; your own language, your own songs and jokes. For such a person, the family disappears...”168 Nevertheless, the peasant “leaven” for many turned out to be stronger than superficial negative influences. The preservation of good traditions was also facilitated by the fact that during the retreat, peasants, as a rule, stuck to their fellow countrymen - due to artelism in work and life, mutual support in certain professions. If the otkhodnik acted not in an artel, but individually, he still usually settled with fellow villagers who had moved completely to the city, but maintained close ties with their relatives in the village.

The public opinion of the peasant environment retained its strength here to a certain extent. Along the roads of settlers and otkhodniks, pilgrims and walkers with petitions, buyers and traders, coachmen and soldiers, the Russian peasant walked and traveled through his great Fatherland. With passionate interest, he listened at home to news about what was happening in Rus', talked about them and argued with his fellow villagers. At a community meeting, he decided how best to apply the old and new laws to his peasant affairs. He knew a lot about the past of Russia, composed songs about it, and kept legends. The memory of the exploits of his ancestors was as personal and simple to him as the instructions of his fathers about the courage of a warrior. The peasant was also aware of his place in the life of the Fatherland - his duty and role as a plowman and breadwinner. “A man has a bag, he has a loaf of bread, he has everything,” an old peasant from the Amginskaya settlement in Eastern Siberia told the historian A.P. Shchapov in the 70s of the last century. “The bread is his money, his tea is sugar. A man is a worker, his work is his capital, his purpose from God.”

Shchapov also recorded the statement of another peasant from the Podpruginsky village on the same topic: “Men are not merchants, but peasants, arable workers: they don’t have to accumulate capital, but to generate the income necessary for the house, for the family, and for good labors to be verbally honored in the world, in society." Respect for one’s work as a plowman and awareness of oneself as part of a large community of peasants in general, men in general, for which this occupation is the main one, was often accompanied by a direct assessment of the role of this activity in the life of the state and the Fatherland.

This happened, in particular, in the introductory part of petitions. Before proceeding to present a specific request, the peasants wrote about the importance of agricultural labor in general. Thus, the peasants of the Biryusinsky volost of the Nizhneudinsky district wrote in 1840 in a petition addressed to the inspector of state property: “Peasants by nature are destined to have a direct occupation with agriculture; arable farming, although it requires a lot of tireless work and vigilant care, but in the most innocent way rewards the peasant farmer for his efforts a satisfied reward with fertility, to this the vigilant authorities repeatedly gave encouragement and compulsion with their instructions, which continue to this day in the Highest Will.”

The term “otkhodniki” appeared long before this mass phenomenon became common throughout the Russian Empire. Temporary, most often seasonal, work provided peasants with a rare opportunity to improve their financial situation and achieve more for themselves and their families.

Otkhodniki. Definition

Compared to ordinary peasants who lived from their own plot of land, otkhodniks were people who were engaged in handicraft work or who sold their labor on the side. This separate social stratum, which arose already in the middle of the 17th century, quickly increased the number of its members, and by the first half of the 19th century this phenomenon had become widespread. Peasant otkhodniks are people who left villages and villages and headed to cities, where industry had just begun to develop and there was an opportunity to earn money in various sectors of the economy.

Who are otkhodniks?

The first otkhodniks were peasants who went to other places for seasonal work. Unknown master craftsmen went to the cities with their simple tools and created wonderful masterpieces of stone and wooden architecture in ancient cities.

The expansion of the borders of the Russian state required the constant strengthening of cordons and the construction of new cities and fortified points. Such work required a constant influx of labor, which only otkhodnik peasants could provide. This phenomenon was especially evident during the construction of new cities in the north-west of our country, including the new capital of the empire - St. Petersburg.

Okhodniks in the 17th-18th centuries

The legal prerequisite for the mass exodus of peasants from their places of residence was the decree of 1718, which replaced household taxation with an income tax. All males were considered taxable. Extortions in kind were replaced by financial obligations, and it was quite difficult to earn any amount in their native village. The opportunity to make money at local plants and factories was practically absent - industry was just beginning to develop, and the main impetus for economic development was given by the influx of foreign capital. The equipment for Russian plants and factories was mainly imported; the main transport routes were seas, rivers, and proven trade roads, so large enterprises arose at first only in

The work of otkhodniks was seasonal and regulated by internal documents - passports. Typically, such a passport was given to a peasant for a year, but there were other certificates whose validity period was shorter. Usually in early spring the otkhodnik went to the city. It took many thousands of kilometers to get there; the otkhodnik often walked the entire route. Along the way I often had to beg for alms. In the city, a peasant otkhodnik was hired as a worker in a private house, an enterprise, or performed one-time work for a one-time payment.

Prerequisites for otkhodnichestvo in the 19th century

In the second half of the 19th century, it was carried out according to which peasants received personal freedom. But the land on which they worked still remained in the possession of the landowners. The proportion of landless peasants who could no longer feed themselves or their families increased. On the other hand, growth gave impetus to the development of industry, which was traditionally concentrated in the city. Thus, the only opportunity to earn money remained in the city.

Attempts to limit otkhodnichestvo

By the middle of the 19th century, otkhodniks were the name given to a huge number of peasants who chose an urban lifestyle. In some provinces, the number of people who preferred otkhodnichestvo reached a quarter of the adult male population. The decrease in the number of peasants working the land forced the government to introduce restrictions. In order to receive an internal document allowing movement around the country, the peasant had to be a member of a rural community; the right to leave the land was bought from the landowner by paying a quitrent. But control measures brought only partial results. For example, after legislative innovations in 1901 in the Lyubimsky district of the Yaroslavl province, out of 12,715 otkhodniks, only 849 peasants returned to the village.

Stratification of society among otkhodniks

The economic rise of the Russian state in the second half of the 19th century launched the process of property stratification of all social strata of the population. The richest otkhodniks are the owners of real estate, hotels and restaurants, shops and wholesale warehouses. Such representatives of the large commercial bourgeoisie occupied about 5% of the total number of otkhodniks.

Up to 70% were representatives of the new urban philistinism, employed in industry, manufacturing, construction and other sectors of the economy. Finally, about a quarter of the total number of this category of the population were hired workers with land plots. Such peasants combined seasonal earnings with cultivating their own land plots.

New life

News of possible earnings was brought to the village by otkhodniks. This event was significant in the life of every village. Returning to their native village from distant cities, otkhodnik peasants changed both their lives and the lives of their families. The way of rural life was changing, the structure of one’s own home was more modern. The influence of the city broke the usual foundations of the village. Unlike other peasants, the otkhodnik is a practically teetotal master and craftsman who has excellent mastery of his craft. The otkhodniks brought amazing household and even luxury items from big cities to their home - kerosene lamps, samovars, furniture, fashionable clothes, gramophones. Local peasants associated all this with a carefree city life. For the girls from this it was an enviable match. By connecting her life with such a husband, a representative of the fair sex could hope for a settled life and a high social status.

OTKHODNICHESTVO – temporary departure of peasants from their places of residence to work in the cities and for agricultural work in other areas. In Russia it has become widespread since the end. 17th century due to the strengthening of the feudal lords. exploitation and increasing the role of money. . It was also noted earlier among the quitrent peasants (burlachestvo, cabbies), and among the Chuvash. peasants have been known since the middle. 18th century (work at copper and iron ore enterprises in the Urals). In the 1st half. 19th century expanded due to ship and barge work. Significant became widespread after the abolition of fortress. rights. In 1897–98 in Alatyr., Buin., Kurmysh., Kozmodemyan., Tetyush., Civil., Cheboksary., Yadrin. In the districts there were, respectively, 4022, 1622, 29, 2064, 975, 1639, 1365, 2213 otkhodniks, which accounted for 8.1% of the working-age men. population of these counties. The main directions of O. were the Urals and Siberia (factories and mines), Simbir., Samar. province (agricultural work), as well as the construction of railways. roads (Kazan-Ryazan, Ural, etc.), enterprises of Kazan and Nizhny Novgorod, Baku oil fields, Donbass mines, salt and fishing. crafts of Astrakhan. Chuvash, who did not speak Russian. language, they were more often hired by the Tatars. Earnings ranged from 30–40 rubles. per season up to 150 rubles. in year. The development of O. contributed to the spread of literacy and knowledge of Russian. language, broadened the horizons of peasants, contributed to the introduction of commodity money. relations in Chuvash. village, increased the standard of living and changed the peasants. everyday life

O. acquired a massive scale during the period of industrialization of the country and collectivization of villages. farms. On June 30, 1931, the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR adopted a resolution “On otkhodnichestvo,” which provided benefits to peasants who left under industrial contracts. construction. In 1933–34, in order to strengthen collective and state farms, a number of decrees were issued prohibiting unauthorized farming. In the post-war period. O. period gradually developed into mass migration of villages. population (especially young people) to cities. After 1965, when enterprises were given the opportunity to create wage funds. boards, the so-called coven. Due to the high density of villages. population, seasonality of labor and relatively low earnings, collective farmers of Chuvashia went to work in the cereals. cities and the Lower Volga region (collecting tomatoes, watermelons, sunflowers). Collective farms hired brigades of “shabashniks” to build farms and other villages. structures. O. in this form the official. authorities regarded it as negative. phenomenon (resolution of the Council of Ministers of the USSR of June 19, 1973 “On the regulation of collective farmers’ labor for seasonal work”). In con. 20 – beginning 21st centuries times care. from places of residence to work in other areas acquired a significant amount. scale.